| our challenge

If there were only one government for the entire Pacific Northwest, saving wild salmon might be a lot easier, and we could achieve our goal with a lot fewer committees and meetings.

But salmon swim through multiple states, through dozens of counties, towns, Indian reservations, and water districts, and even into the waters of more than one country. The result is that there are over 800 government jurisdictions and agencies involved in salmon recovery.

And, of course, salmon swim past many privately-owned forests, farms, orchards, vacation homes, suburbs, and cities. Everyone who owns land near a river or stream is affected by efforts to save wild salmon. And every citizen is, too, since we all share responsibility for the dams that produce our electricity, the streets that we drive on, the chemicals we put on our lawns, and the water and sewer services we use.

The number of governments, farms, businesses, homeowners and other citizens involved in salmon recovery presents a special challenge: To save wild salmon, we must coordinate the actions of all these agencies and people.

That's why partnership is such an important theme at every level of government and in every watershed in Washington state.

|

our progress

The Governor's Joint Natural Resources Cabinet has tried to set a high standard of collaboration, coordination, and mutual support with our myriad partners. The agency directors, their staff and the Governor's Salmon Recovery Office regularly work with local and tribal governments, farmers, business leaders and citizens across the state.

The state legislature has also pushed for local partnerships and the empowerment of local citizens. Efforts to save salmon must begin one river at a time, and one community at a time. Although the imperative to save threatened and endangered species is a national commitment, embodied in the Endangered Species Act, the work called for in that Act can only be achieved locally.

The legislature has recognized the key role of collaborative action in the three major bills it has enacted:

- The Salmon Recovery Funding Board supports local partnerships by funding habitat protection and restoration projects that are proposed by local groups established under the Salmon Recovery Planning Act. Five citizen members were appointed by the Governor in 1999: Bill Ruckelshaus as Chair; Frank "Larry" Cassidy, Jr.; Brenda McMurray; James Peters; and Hon. John Roskelley. They are assisted by the state directors of the Washington Conservation Commission, Department of Ecology and Department of Fish and Wildlife; Commissioner of Public Lands; and Secretary of the Department of Transportation.

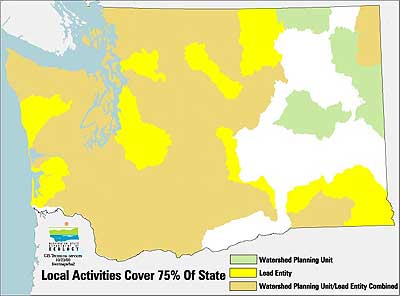

- Lead Entities for Salmon Recovery were established by the Salmon Recovery Planning Act (known by many as "2496" after its legislative bill number) in 1998. The Act focuses on the need for coordinated local action to restore habitat conditions necessary for salmon recovery. Lead Entities spearhead these local efforts. Some of the Lead Entities are the same as the watershed planning groups created by the Watershed Planning Act, but in other areas water planning and salmon recovery efforts remain separate. To date, 25 lead entities covering 45 watersheds have been created.

|