| our challenge

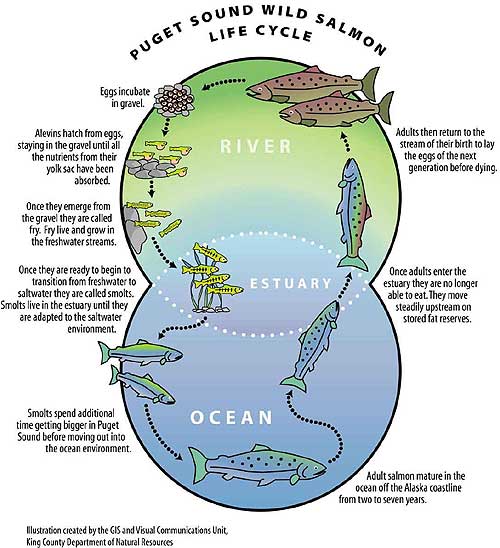

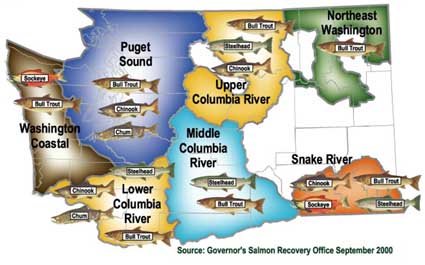

Pacific salmon have disappeared from about 40 percent of their historical breeding ranges in Washington, Oregon, Idaho and California over the last century. Today, 15 runs of wild salmon have been federally listed as threatened or endangered across 75 percent of Washington state. The reasons for the decline are long term and complex. We over fished, and hatchery fish competed with wild fish for limited space and food. Beyond that, human activity has radically changed the physical landscape and habitat of salmon in the last 150 years. And as growing numbers of people take water from rivers, there is less water to supply the needs of salmon.

Today, the listing of some of Washington's wild salmon under the Endangered Species Act provides a fresh opportunity-indeed, a fresh and compelling mandate-to try harder, to do more, and to learn more about this icon of the Pacific Northwest.

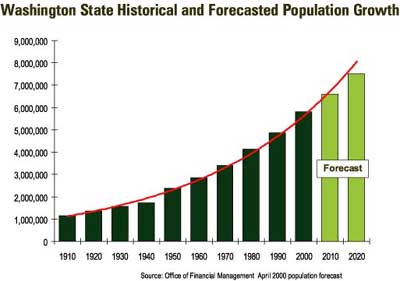

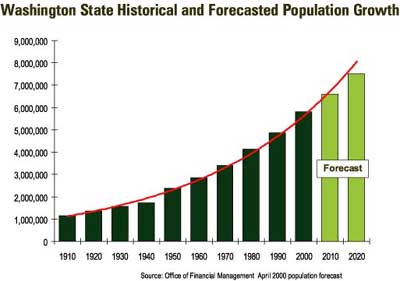

The scale of this challenge is enormous. In the next fifty years, the population of Washington is likely to double, placing even more stress on our water supplies and our land. At the same time, each of us consumes more natural resources than ever before. For example, while the population in Central Puget Sound grew by 36 percent between 1970 and 1990, the amount of developed land grew by 87 percent. The cumulative impact of bigger houses and suburban lots, more paved roads, parking lots and shopping malls is taking a heavy toll on rivers and streams and the fish that live in them.

|

|

Our task is further complicated by the complex relationships between Washington state's economy and the land and water that are so critical to the health of salmon. This will require consideration of the economic costs and benefits of recovery activities, so we can ensure that a healthy salmon population and continued economic vitality go hand in hand.

The Endangered Species Act provides powerful new incentives to rise to this challenge. It says, in effect, that if we don't do this ourselves, the federal government and federal courts will step in to prevent further harm to endangered and threatened runs of salmon. This could mean that the federal government would make local decisions ranging from when and where new roads, houses and businesses can be built, to how much water farmers can use to irrigate their crops.

If the people of Washington want to control our own destiny, we simply must make the investments of time, energy and money necessary to change our impacts on the natural systems that affect wild salmon.

|