Fishing has been a way of life for Washington people for thousands of years. For local tribes, salmon were both sustenance and spiritual equals in the web of life. For immigrant settlers, Washington's abundant waters were an opportunity to sustain fishing traditions, and to build new lives and communities in the far frontier of the American west. Fishing-especially fishing for salmon- has also been one of the defining recreational experiences of growing up in Washington for millions of youngsters over many generations.

Needless to say, cooking and eating salmon are a signature of life in the Northwest. In any gathering of people, a stranger can always strike up a conversation simply by asking about the best way to cook this fish.

Salmon have a high profile, and for many who live here, fishing has been considered a major cause of their decline. One early response to the decline was to build hatcheries to produce more fish. But even the most productive hatcheries in the world cannot make up for the continuing shrinkage in the amount of clean, cold water and unobstructed streams accessible to migrating salmon.

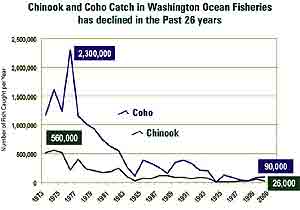

While hatchery fish sustained-and in some cases increased- the fish available for harvest, the abundance of hatchery fish masked the problems of dwindling and degraded freshwater habitat for wild fish. It also created another problem. When fishers caught hatchery fish, they were at times mixed with wild salmon stocks. The result is we over-harvested wild fish that were in trouble.