Freshwater and estuarine habitats are healthy. Rivers and streams have flows to support salmon. Water is clean and cool enough for salmon. Compliance with resource protection laws is enhanced.

Habitat

| our goal

Freshwater and estuarine habitats are healthy. Rivers and streams have flows to support salmon. Water is clean and cool enough for salmon. Compliance with resource protection laws is enhanced. |

|

| our challenge

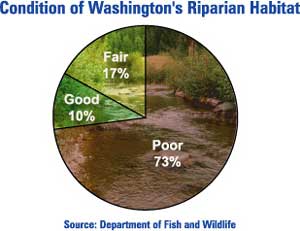

The salmon's plight is the result of many decades of decline, caused by many factors. Much of our freshwater rivers and streams where salmon begin and end their lives have been diked, diverted, channeled, polluted, or blocked to meet the needs of agriculture, industry, and homes. Over 1,000 dams impede salmon on their journey to the sea and back. Some of our rivers no longer carry enough water to support salmon in late summer. In winter, we have more scouring floods that destroy salmon eggs and wash young fish out to the sea because of increased urban development. Urbanization has also been a major factor in the loss of river estuaries-the broad, often meandering and braided areas where rivers empty into saltwater. In the past, river estuaries provided important shelter and feeding grounds not only for wild fish, but for many other species of plants and wildlife, too. Sixty percent of our state's estuaries have been lost as rivers have been channeled, and over half of the 40 percent that are left are in only fair or poor condition. Urban stormwater-the water that runs off streets, roofs, parking lots and other hard surfaces-creates a different kind of water problem: when it rains, water is quickly dumped into streams, lakes and marine waters instead of soaking into the ground. In many areas, this water contributes to more frequent floods-floods that can wash young salmon out to sea, destroy salmon eggs in streams, and pollute water with contaminants from streets and parking lots. |

|

|

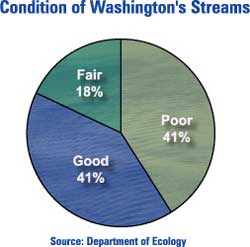

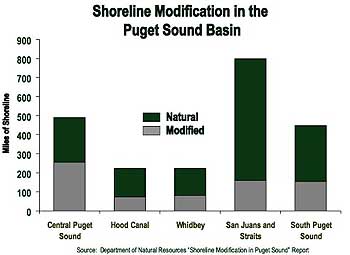

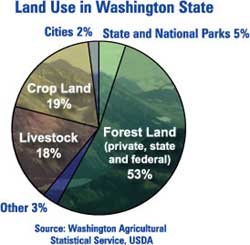

Urbanization presents many other challenges, too. Forest and farm land is being converted by urban development at a growing rate. For the four most populous counties in Puget Sound, the rate of urbanization has doubled in the last 25 years, from 150,000 acres per year in 1970 to 300,000 acres per year in 1995. Puget Sound shorelines have been extensively altered by bulkheads, filling, dredging, and other development impacts. Because of the many demands placed on some rivers and streams to meet our needs for water, one of our most difficult challenges will be finding ways to restore water to streams where and when it's needed for salmon. Most farmers, cities, and industries have long standing water rights that entitle them to special status as "prior appropriators." This means that their rights to water come first, and they can take all the water they have a right to without leaving adequate amounts for fish. This is the legacy of 19th century frontier laws that resulted in a "first come, first served" legal basis for establishing water rights. Oddly enough, salmon were not accorded a legal right to water until 1967. This means that even if new state laws require that a certain amount of water must be left in streams for fish, the prior appropriators will not be affected because their rights were established first. In many areas, we simply don't know enough about the quantity and condition of the water in streams to manage it well. We do know that there are 645 streams, lakes, and marine areas listed on the state's water pollution list; about 55 percent of these have been degraded by agricultural activities, 20 percent are affected by municipal wastewater. Additionally, 30 percent have been degraded because the areas near their banks have been damaged. In the last 30 years, the legislature has given Washington many valuable environmental laws: the Growth Management Act, the Shorelines Management Act, the Hydraulics Act, and the State Environmental Policy Act. Congress has passed the Clean Water Act and the Endangered Species Act. All are important tools in salmon habitat protection. But their implementation requires coordination across many government agencies, often with competing missions. This contributes to confusion and frustration on the part of people who try to get permits to do their projects. And putting protective conditions on permits issued under these laws raises the thorny issue of private property rights versus environmental protection. What each of us does on our own land affects our neighbors and the quality of the environment around us. Finding the right balance between individual property rights and the public interest in protecting our environment will continue to be among the most difficult challenges facing federal, state and local agencies. |

| our progress

Forests and Fish The Forests and Fish Agreement is a voluntary pact negotiated by small and large forest landowners; federal, state, tribal and county governments. It covers eight million acres of private forest land, protecting 60,000 miles of streams. It is the first agreement of its kind in the country, winning the approval of the federal agencies that enforce the Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act. The Agreement became state law by the 1999 Legislature. This landmark law establishes new rules for forest practices-rules that do a better job of protecting salmon habitat and providing for restoration of streams that have been damaged by past harvest practices and logging roads. It requires timber harvesters to leave uncut buffers along streams so that banks are not damaged and the water stays shaded and cool. It establishes protections for forested wetlands, limits logging on steep slopes to prevent erosion, requires well-maintained roads, and calls for repair or removal of culverts that block fish passage. |

Financial incentives were established to help small landowners adapt to the provisions of the Agreement, and a Small Forest Landowner Office has been created within the Department of Natural Resources. Even more important, the agreement includes an "adaptive management" provision-a provision that says, in effect, if scientists determine that these measures prove insufficient, everyone will look at what more needs to be done. This adaptive management provision is a new and powerful way to ensure genuine progress for salmon recovery in the 53 percent of Washington's land area that is covered by forests. However, not everyone feels that the Forests and Fish Agreement is sufficient to protect salmon. In September 2000, environmentalists and commercial fishers filed a lawsuit against the federal government challenging the Agreement. The state supports Forests and Fish and will join the federal government in defense of it. |

|

| Just what is this thing called habitat?

Simply said it's what fish need to live; it's where they live. It's clean, cool water in the right amounts. It's the trees and shrubs that shade streams and help filter pollutants that enter the water. And because fish and people share the same habitat, everything we do in managing our land and water affects salmon. |

| Agriculture, Fish and Water

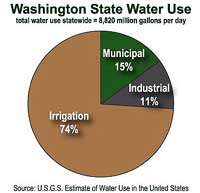

A negotiation similar to Forests and Fish is now underway with agricultural interests, irrigation districts, local, state, and federal governments as well as some environmental and tribal participation. Since agriculture accounts for 37 percent of Washington's total land area and 74 percent of our water usage, this is an important effort. And it's the first time the agricultural community has participated in a statewide negotiation-another visible example of the way salmon recovery is bringing diverse interests together. Negotiators have reached agreement on basic principles and concepts and are now working on specific conservation practices and guidelines to help agriculture voluntarily address water quality, quantity, and habitat issues that limit salmon recovery. |

|

The negotiations are proceeding on two fronts: First, work is underway to revise conservation practices used in developing individual farm management plans. The changes will be reflected in the updated Field Office Technical Guide, developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Second, negotiators are working to develop new planning guidelines that will help irrigation districts address water quality and water conservation issues. |

|

Both negotiation processes are working toward meeting Endangered Species Act requirements and Clean Water Act standards, providing regulatory certainty on both issues. The negotiated agreement also must assure the long-term economic viability of agriculture in Washington state. While these negotiations are underway, changes already are taking place. State and federal funding of the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program has made it possible to pay landowners to restore and protect 600 miles of streamside habitat in agricultural lands (and other privately-owned land) adjacent to streams where salmon reside. Individual irrigators are also investing in new methods of water conservation and farm practices. For example, Yakima River basin irrigators have successfully reduced sediment in the river-a major water quality problem-by 25 percent. And dairy farmers are changing practices to keep dairy waste out of streams. Working with conservation districts, 34 percent of the dairy farms developed "nutrient management" plans and are now working to get them certified and implemented. |

|

Water Quantity and Quality

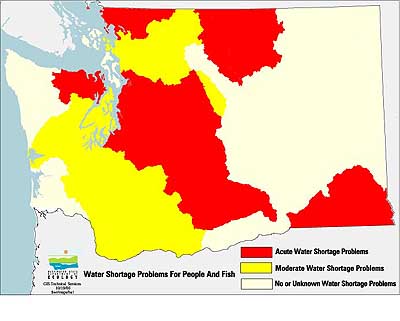

The 1998 Watershed Planning Act (known by many as "2514" after the legislative bill number that created it) gives incentives for local citizens to assess the health of local watersheds and develop plans to restore and manage them with the health of salmon in mind. Of the 62 "water resource inventory areas" in the state, 40 are now developing such plans; eleven of these are in river basins where there currently is a known shortage of water for people and fish. To help local citizens determine how much water is needed in streams to keep fish healthy, state agencies are providing funding and assisting in studies on the amount and quality of water in many of these watersheds. A combination of strategies to increase the amount of water in streams will be needed: aggressive conservation by all water users; finding ways to re-use water for golf courses, street cleaning, and industrial cooling and heating; and identifying environmentally sound water storage opportunities that will allow release of water to augment historically low flow periods. |

|

|

State and federal governments are now negotiating cooperative agreements with water rights holders near rivers that need more water. In some cases, the state will actually buy water from them to leave in the rivers for fish.

Work is also underway to revise water quality standards to address salmon's sensitivity to the temperature of the water, and to ensure that streams are cool enough to keep salmon healthy. Water clean-up plans are being developed for each of the 645 polluted water bodies; last year 56 of these plans were completed, bringing the total to 216. All plans will be done by 2013, in accordance with a schedule approved by the federal Environmental Protection Agency. State agencies are also more assertive in enforcing existing laws against water pollution and unauthorized use of water. Actions have been taken against illegal water use, and new partnerships have been established with property owners who agree to work with local conservation districts to halt and repair stream degradation. During the last four years, $3 million in water pollution fines has been levied against persistent polluters-a 100 percent increase over the previous four years. |

| Fish Passage Barriers

There are big cumulative gains for salmon when culverts and other barriers that fish can't navigate are removed. In both urban and rural areas, preliminary studies estimate that a total of somewhere between 2,400 and 4,000 culverts and other barriers now block salmon access to 3,000 to 4,500 miles of freshwater spawning and rearing habitat. Of the barriers that have been created in the course of road-building, 10 percent are estimated to be on state highways, 40 percent on county, city and town roads, and about 50 percent are on private and forest roads. Other barriers such as dikes, levees, and floodgates can also stop fish migration. Correcting these fish passage barriers can be one of the most cost-effective ways of restoring more habitat for salmon. Fixing a single culvert can open many miles of a stream for spawning and rearing young fish when there's good upstream water and riparian conditions. Many government agencies, environmental groups and civic organizations are involved in the repair, removal or maintenance of culverts and other barriers as part of their habitat restoration efforts. For instance, the Washington State Department of Transportation has inventoried 2,300 culverts under state highways, and found that 30 percent of them block a total of 508 miles of streams that could provide salmon habitat. So far, they have fixed 59 of them. |

before  after |

To help this process along, new manuals on fish barriers, screening for surface water diversion, fish ladders and fish-friendly culvert designs have been produced. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife is providing extensive technical assistance and support to other state agencies, counties, cities, tribes, irrigation districts and private landowners. And various government agencies and private donors are providing grant funding to accelerate progress in barrier removal. Projects funded by the state's Salmon Recovery Funding Board and carried out by local citizens and organizations opened up 180 miles of stream habitats during the summer of 1999. There are over 60,000 places where water is diverted from Washington's streams, rivers, and lakes for irrigation or other uses. Screens are needed at these locations to keep fish from getting swept into the diversion and becoming lost, stranded, and destroyed. The majority of these diversions are either not screened at all, or have screens that are inadequate. 1998 studies showed only 48 percent compliance with screening regulations. These problems are being addressed with stepped up inspection and enforcement actions, more technical assistance, education, and systematic efforts to identify, prioritize and fix inadequate screens. Last year, screening efforts concentrated in the Methow Valley. Funding was provided by the Salmon Recovery Funding Board to assist the installation of three large screens on major diversions in the valley. Progress will remain slow, however, because the needs outstrip funding available to accomplish the task. |

| Balancing the needs of farmers, fish,

business and ordinary people will not

be easy Anything worth doing is rarely simple."

|

Designed to provide boat passage and regulate lake water levels between sea-level Puget Sound and higher-elevation fresh waters, fish passage was not a major consideration when the Ballard Locks were constructed nearly 90 years ago. Attention has turned in recent years to the toll this man-made marvel takes on fish. A scientific task force recommended changes in both operations and facilities to make the locks more friendly to the millions of fish that make their way from rivers and streams feeding Lake Washington on their way to the ocean. This year, four new smolt slides (upper right) provided fish with a safer alternate passage, allowing them to follow water flow and glide unharmed past the locks. |

| Urbanization, Land Use and Stormwater

State and local governments are working now to rewrite guidelines for dealing with stormwater runoff. Separate stormwater guidelines are being written for Eastern and Western Washington that will recognize the differences between these distinct regions; the Western Washington guidelines will be completed this winter. They will be aimed at reducing stormwater runoff from new developments, and improving the way stormwater is collected and discharged into streams, lakes, and marine waters. Already many cities and towns have changed requirements for new development so that more land is left unpaved to allow water to soak into the ground. But a growing population and rapid urbanization-especially in Western Washington-make this a difficult challenge. To help protect shorelines and support salmon recovery in an era of rapid population growth, the state's Department of Ecology is adopting new shoreline management guidelines. These new guidelines, updating 28 year-old rules, have been reviewed by the public in meetings around the state, and were completed in November. The new guidelines allow local communities to choose one of two paths. They can adopt a shorelines master program using a set of guidelines approved by federal agencies responsible for enforcing the Endangered Species Act, or they can customize their plans and negotiate individually with the federal agencies for ESA certainty.

|

Because of state laws, local governments are defining urban growth boundaries, protecting remaining wetlands, estuaries, and forest and agricultural lands, and adopting shoreline protection programs. In most areas, we need to first protect the best of what's left, then work to restore what's been degraded. This means placing a high priority on reducing further degradation of stream health and water quality, then working to restore as much of the damage that has been done as is possible. This can be achieved by protecting wetlands and unstable slopes, acquiring key parcels in fee or easement, leaving adequate buffers along streams, reducing stormwater discharge, preventing erosion during construction, and changing landscaping to reduce water and polluted runoff. The current condition of salmon suggests we need to continue these efforts. But we also need to examine how government agencies with overlapping responsibilities for environmental protection can lessen confusion and frustration on the part of people attempting to obtain permits. In all of these efforts, it is clear that regulation alone won't suffice. Private streamside and waterfront landowners, other citizens, and business owners all must play a role in addressing the impacts that threaten wild salmon. There will be a continuing need for incentives, technical assistance and public education about the importance of changing the way we build new houses and businesses, maintain our lawns, and care for the streams in our communities. That's why state, federal, tribal and local governments are working at every level to encourage a new kind of cumulative impact-the cumulative benefit of thousands upon thousands of urban residents using less water, retaining or planting more trees, putting fewer chemicals on the lawn, and choosing to live in higher-density housing in order to preserve more habitat for salmon and more open space for generations to come. |