IV. Core Elements

Habitat is Key

AGRICULTURAL STRATEGY TO IMPROVE FISH HABITAT

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Considering that agricultural lands comprise 37 percent of our state and represent approximately 74 percent of water use state-wide, it’s no surprise that agriculture plays a significant role in the recovery of Washington’s salmon. Approximately 37,000 farms cover 15.7 million acres and produce more than 200 commodities, such as apples, milk, hay, berries and Christmas trees. More than half of these farms are smaller than fifty acres, while others are large corporate entities. Large and small farms combined provide thousands of jobs and contribute billions of dollars to our state’s economy.

Unfortunately, agricultural activities sometimes contribute to the degradation of water quality and reduction of water quantity; both of these can significantly affect salmonid habitat. Activities which remove riparian habitat along streams, or that add excessive amounts of nutrients and silt to water, contribute to the increasing numbers of water bodies not meeting water quality standards. These activities also play a role in the listing of several salmon, steelhead and trout populations as threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act (ESA).

Most existing state and federal laws and regulations dealing with agricultural practices apply incentive-based approaches and rely largely on providing technical and financial assistance to farmers. Most program delivery is through local Conservation Districts in partnership with the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS). The Washington State Conservation Commission provides grant funds to the Districts to implement local conservation practices, and NRCS staff provides technical assistance to private landowners. They also join with Conservation District staff to help landowners develop management plans that protect resources, as well as the landowner’s economic interests.

In addition, the State Conservation Commission funds a variety of water quality projects using state Centennial Clean Water funds. These projects are implemented by local Conservation Districts. The Department of Ecology also funds agricultural water quality and quantity projects.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goal

·

Improve farm and sector-based practices to provide the water

quality, water quantity, and functional riparian habitat needed for salmon

recovery in the agricultural sector.

Objectives

·

Revise the

Field Office Technical Guide (FOTG) to provide the tools needed to enhance,

restore and protect habitat for fish and to address state water quality

standards.

·

Ensure that

there is thorough stakeholder participation in the process of revising the

Field Office Technical Guides under the Natural Resource Conservation Service’s

Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with state and federal resource agencies.

·

Raise the

awareness and understanding in the agricultural community of salmon recovery

and watershed health, and build support for the agricultural strategy and its

implementation.

·

Support

agricultural organizations’ and associations’ efforts to implement the

agricultural strategy and to help communities and general public understand and

support this effort.

·

Fully implement

the Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP) and expand its scope to

include tree fruit, berries and grapes.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

The agricultural

strategy builds on the infrastructure used for the last 40 years to implement

conservation practices on farms. This system has relied on voluntary actions

and incentives, with technical assistance and cost-share money provided by the

Natural Resource Conservation Service and state Conservation Districts. The

Strategy will encourage comprehensive programs in those areas most in need of

protection and restoration.

The first priority

of the strategy is to review and, if necessary, upgrade the conservation

practices currently used by the Conservation District — Natural Resource

Conservation Service partnership. These standards will address water quality

and fish habitat on farms and are designed to provide upgraded conservation

standards that meet Endangered Species Act (ESA) and Clean Water Act (CWA)

requirements. Conservation Districts and the Natural Resource Conservation

Service will use these to develop farm plans that will be the mechanism used to

address water and fish habitat quality. Federal and state programs will be used

to provide technical assistance and cost-share money to help farmers implement

the practices. The program will use conservation practices from the Natural

Resource Conservation Service’s updated Field Office Technical Guide. A second

component of this effort is a guidance document to assist irrigation districts

in developing comprehensive plans that address their ESA-related concerns. This

effort is known as the “Agriculture, Fish and Water” (AFW) forum.

A second cornerstone

of the strategy is implementation of the Conservation Reserve Enhancement

Program (CREP). The program is a joint effort between Washington state and the

U.S. Department of Agriculture to restore fisheries habitat on private

agricultural lands adjacent to depressed or critical salmon streams. The

program has $250 million in funding, enough to restore between 3,000 and 4,000

miles of degraded riparian habitat.

The strategy also

relies on a commitment by the state to enforce existing environmental laws and

regulatory programs. It includes better tracking and accountability than in the

past and calls for monitoring and adaptive management. Benchmarks will be set

to measure success, and if they are not met within three years the state will

seek new authority from the Legislature to ensure salmon protection in

agricultural areas.

The strategy also

encourages sector-based approaches such as commodity groups or irrigation

districts developing Habitat Conservation Plans. The state will provide

technical and funding support to groups developing these comprehensive

commitments.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

The

Conservation Districts and NRCS will implement monitoring at the local level.

The state Conservation Commission will develop a statewide database to track

implementation by watershed, or Water Resource Inventory Area (WRIA), region or

statewide. An oversight committee will develop a process to assess the success

of implementation.

An

effectiveness monitoring system will be designed to ensure conservation

practices are working. This will be part of an overall monitoring strategy used

by the state to measure success in providing clean water and good physical

habitat.

Habitat is Key

FORESTS AND FISH

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Roughly

half the land area in Washington, about 21 million acres, is covered by forests.

Nearly 12 million of these are non-federal forest lands owned by large and

small private landowners and the state of Washington, and managed primarily for

timber production. Forest management practices on these state and private lands

have been regulated since 1974 under the State Forest Practices Act,

administered by the Department of Natural Resources (DNR) with rules co-adopted

by the Forest Practices Board and the Department of Ecology.

Most

salmon-bearing streams in Washington have their headwaters, and in many cases a

majority of their watersheds, in forested areas. Studies have consistently

shown that streams flowing from forested areas are healthier than streams

flowing from agricultural lands or developed areas. On the other hand, forest management

activities such as road building and timber harvest near streams or on steep or

unstable areas can damage fish habitat and water quality. Impacts from these

forest practices are among those contributing to the listing or proposed

listing of some salmon runs.

Protecting

water quality and fish habitat has always been an objective of forest practices

regulations. Since 1986, state, tribal, environmental, citizen and industry

leaders concerned about forest management on state and private lands have formed

a consensus-based negotiating forum known as Timber, Fish and Wildlife (TFW),

which has developed scientifically-based proposals for new regulations. The

listings of salmon runs as threatened or endangered prompted TFW participants,

with the addition of federal and county representatives, to launch in 1997 a

new round of negotiations. Participants sought to create strengthened

regulations and other measures necessary to meet fish conservation requirements

of the Endangered Species Act (ESA), as well as water quality requirements of

the Clean Water Act (CWA), while maintaining a viable timber industry and

providing long-term regulatory certainty.

The

Joint Natural Resources Cabinet requested the Forest Practices Board in 1997 to

transmit its salmon and water package (originally termed the “Forestry Module”

and now known as Forest and Fish Report) for inclusion as the forest habitat

component of the Statewide Strategy to Recover Salmon.

Negotiations

took place until September, 1998 through Timber, Fish and Wildlife, and

continued after then with all participants except representatives of

environmental organizations. Forestry Module negotiations resulted in the

Forest and Fish Report submitted to the Forest Practices Board and the

Governor’s Salmon Recovery office on February 22, 1999. The report was

finalized on April 29, 1999 and is now an integral part of the implementation

of the statewide strategy.

The

1999 Legislature passed Engrossed Substitute House Bill 2091 (ESHB 2091),

“An

Act Relating to forest practices as they affect the recovery of salmon and

other aquatic resources.” Section 101 of states that the Act:

“Constitutes a comprehensive and coordinated program to provide substantial and sufficient contributions to salmon recovery and water quality enhancement in areas impacted by forest practices and are intended to fully satisfy the requirements of the endangered species act with respect to incidental take of salmon and other aquatic resources and the Clean Water Act with respect to nonpoint source pollution attributable to forest practices.”

The Act establishes

legislative direction to the Forest Practices Board for using the Forest and

Fish Report to protect salmon habitat and water quality.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goals

·

Strengthen regulations to restore and maintain habitat to

support healthy, harvestable quantities of fish.

·

Strengthen regulations and other measures necessary to meet

fish conservation requirements of the Endangered Species Act, as well as water

quality requirements of the Clean Water Act.

·

Maintain a viable timber industry and provide long-term

regulatory certainty.

Objectives

The

Forest and Fish Report and ESHB 2091 are designed to deal with the following

topics:

·

Riparian protection for fish habitat and non-fish habitat

streams

·

Mandatory improvements for existing and new roads

·

Protection for unstable slopes

·

Application to small landowners

·

Use and modification of watershed analysis

·

Adaptive management

·

Overall funding

·

Assurances and certainty associated with the agreement

Specific

objectives are being developed for each of those listed above.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

The

Forest Practices Board is authorized by ESHB 2091 to take immediate action by

declaring emergency rules to put several of the Forest and Fish recommendations

into effect until permanent rules are adopted. The Joint Natural Resources

Cabinet expects the Board will take this action in late 1999 or early 2000,

with final rules ready for adoption on or before June 30, 2000.

Implementation

of the Forest and Fish recommendations will rely heavily on Geographic

Information System (GIS) mapping and data processes to better protect and

monitor public resources. Transportation, water typing and wetlands mapping and

data layers will assist forest managers in fully evaluating forestry impacts on

salmon.

Developing

conservation strategies for riparian areas, unstable slopes and wetlands will

be the primary but not exclusive focus for achieving forest goals.

Riparian Areas

Riparian

areas will be protected through buffers and limits on management activities

along fish and non-fish habitat streams. Specific requirements vary in western

and eastern Washington, but ecological functions of the streamside habitat are

the primary focus. A new system of water typing will be employed, designating

streams according to availability of fish habitat rather than fish presence.

Roads

The

number of new roads built in riparian areas will be minimized, and construction

and maintenance standards for all new and existing roads will be improved. For

existing roads, enhanced best management practices will be adopted immediately

and road maintenance and abandonment plans will become mandatory. New roads

will be built according to improved sediment and water delivery standards, and

new culverts will be required to meet a 100-year flood standard to ensure

passage of fish and some woody debris. No new roads will be allowed in bogs or

low nutrient fens.

Unstable slopes

The

Department of Natural Resources and the Timber, Fish and Wildlife participants

will screen all forest practices applications to identify and address hazardous

unstable slopes.

Watershed analysis

Watershed

Analysis will be revised to address technical upgrades necessary for compliance

with the Clean Water Act.

Small landowners

A

program for small forest landowners was created to achieve full riparian

protection and to provide financial incentives to small landowners who

volunteer to participate in the Forestry Riparian Easement Program. The program

does not provide an exemption to small landowners, except those with fewer than

20 acres in a parcel and fewer than 80 acres statewide. It is intended to help

assure the viability of non-industrial forest landowners and keep forest land

base in forestry.

A

Small Forest Landowner Office was created by the 1999 legislature to administer

the Forest Riparian Easement Program, and to assist small landowners with

development of options and alternate plans. The Office is required to evaluate

the cumulative impacts of alternate plans on essential functions within the

watershed and make any necessary adjustments. An advisory committee was

established to assist the office.

Wetlands protection

The

objective is to achieve a “no net loss” of forested wetlands functions by

avoiding or minimizing forest practices impacts or by restoring affected

wetlands.

Timber

harvest in bogs is not allowed. The required wetlands mitigation sequence will

be determined based on loss of wetland function, site management plans, and

maps of all forested wetlands — regardless of size — that are associated with

an affected riparian management zone. For the long-term, through the adaptive

management process, a technical group will be convened to better define the

functions of forested wetlands, to evaluate their regeneration and recovery

capacity, and to evaluate the effectiveness of current wetlands management

zones.

Landowners

will map all forested wetlands associated with riparian areas and other

forested wetlands three acres or larger. In addition, the Department of Natural

Resources will incorporate wetlands into a Geographic Information System (GIS)

map layer, depending on availability of funding.

Pesticides

The

use of pesticides will be managed to meet water quality standards and label

requirements and to avoid harm to riparian vegetation.

Best

management practices will be implemented to eliminate direct entry of

pesticides to water. A variable buffer width will be used to keep pesticides

out of water and wetlands. In unfavorable wind conditions, no aerial spraying

will be allowed in a specified wider buffer. With few exceptions, no spray will

be allowed in the no-touch zones or inner zones or to wetland management zones.

In addition, no aerial applications will be allowed within the area of the

inner zone used to meet the basal area and tree density targets. Use of BT is

subject to label requirements.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

Adaptive management

Adaptive

management is critical to implementation of an agreement in areas where

knowledge is currently limited and requirements may need to evolve through

time. Forests and Fish will employ a more formal and structured process than

has been used in the past for monitoring, research and adaptive management to

ensure accountability.

Four

primary relationships will be monitored: correlation between target forest

conditions and goal attainment, effect of forest practices on forest

conditions, effect of forest practices on other resource objectives, and

enforcement (on-the-ground implementation of forest practices.) The Forest

Practices Board will be involved in the process, and a multi-staged dispute

resolution mechanism could be triggered if necessary. A key component of

adaptive management is Timber, Fish and Wildlife’s ongoing Cooperative

Monitoring, Evaluation and Research program (CMER), which incorporates the

scientific foundation for forest practices.

Default mechanisms

Forests

and Fish differs from some other elements of the Statewide Strategy to Recover

Salmon that rely on voluntary or incentive-based approaches to achieve desired

outcomes.

In the case of forest practices, objectives have been pursued since 1974

through the statewide regulatory program embodied in the Forest Practices Act

and evolving forest practices rules. The new rules and other features of the

Forests and Fish report will become in effect the default mechanisms. In

addition, the proposal includes adaptive management measures to ensure

objectives are met over time. Finally, federal regulatory agencies will

implement their authorities to require ongoing achievement of the Forests and

Fish report’s goals.

Habitat is Key

Linking Land Use Decisions and Salmon Recovery

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Population

growth experienced in Washington in the past 30 years has taken a toll on the

state’s environment and natural resources. The population increase has

profoundly affected our natural resources, and impacts associated with

development have drastically altered many natural habitats critical for salmon

survival.

Urbanization

has significantly affected small streams, riparian corridors and associated

wetlands. A great percentage of spawning and rearing habitats in estuaries,

wetlands and streams have been eliminated or degraded. The cumulative effects

from years of human disturbance will take many years to turn around. The

on-going challenge will be developing and implementing strategies in urban and

rural areas to protect and restore habitat while accommodating population

growth, and addressing economic viability in light of restrictions anticipated

for salmon recovery.

The

primary tools for regulating land development are the Shoreline Management Act

and the Growth Management Act, supplemented by the State Environmental Policy

Act. There are other state, federal and local laws and regulations that apply

to various land use activities.

Several

of these laws establish a shared responsibility between various local

governments, between the state and local governments, and with tribal

governments. In addition, there is a wide range of governmental entities and

authorities with a role in land use and environmental decisions.

The

current condition of many salmon populations suggests that most plans, programs

and regulations are not yet fulfilling their goals to protect and preserve

natural resources and the

environment. Current knowledge and understanding of salmon protection and

recovery requires that state and local plans and regulations be updated to

include the best available science. In some instances, more restrictive

regulations and/or economic incentives must be enacted to protect, preserve and

restore salmon habitat. In many other cases, more effective implementation,

mitigation, enforcement and rigorous monitoring of current regulations are

required.

To

effectively respond to the threat to salmon runs, land use issues must be

addressed at the same time as other specific factors such as harvest,

hatcheries and hydropower. No single governmental agency or private party will

be able to solve this problem on its own. State, local and tribal governments

and citizens must work together in a coordinated manner to change those land

use practices that have the most detrimental impacts on salmon.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goal

·

Protect and restore fish habitat by avoiding and/or

mitigating site specific and cumulative negative impacts of continuing growth

and development.

Objectives

·

All counties and cities will revise their Growth Management

Act (GMA) plans and regulations by September 1, 2002, to include the best

available science and give special consideration to the protection of salmon.

·

Ensure implementation of land use practices that protect

habitat and/or have no detrimental impacts on salmon habitat.

·

Focus state and local land use and salmon recovery efforts

first in areas with Endangered Species Act (ESA) listings and areas with

potential for high quality habitat.

·

Promote the use of local incentives and non-regulatory

programs to protect and restore wetlands, estuaries and streamside riparian

habitat.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

Counties

and cities are required on a five-year cycle to review and, if needed, amend

their comprehensive plans and development regulations to conform to the

requirements of the Growth Management Act (GMA) and the Shoreline Management

Act (SMA). In addition, all Critical Areas Ordinances must be developed using

the best available science and give special consideration to the protection and

conservation of salmon.

These

requirements provide an excellent opportunity for local governments to upgrade

the quality of GMA and SMA plans, programs and regulations. They also provide a

higher level of protection of natural resources and remove or address any uncertainties

local governments and private landowners face under the Endangered Species Act

and the Clean Water Act. The state will provide guidelines for locals to use in

meeting these requirements. The first review and revision of plans and

regulations must be completed by September 1, 2002.

The

state will seek collaborative decision-making and will provide incentives to

encourage voluntary efforts, recognizing that there are minimum expectations

that must be met. It will rely on better implementation and enforcement of

existing laws to prevent continuation of land use practices that have negative

impacts on salmon. Where gaps in existing laws are identified, new regulatory

authorities will be sought.

Policy guidance: preserve, protect and restore

Our

state’s growing population has led to development that replaces vegetation,

removes or destroys soil, changes surface drainage patterns, and covers the

land with impervious surfaces. While we can reverse some of the effects of

these developments, it is not feasible to undo many of them, such as replacing

soil or removing roads and buildings.

It

is therefore important that remaining high quality habitat is preserved,

protection measures undertaken, and restoration and enhancement efforts begun.

State and local governments will consider the following policy guidance when

making land use decisions, reviewing and approving plans, adopting regulations

and permitting developments:

·

Preserve high quality habitat and salmon populations through

various methods of land conservation.

·

Protect aquatic ecosystems by using, enforcing and improving

current laws, rules, guidance and incentives for planning, designing,

constructing and maintaining new development and redevelopment.

·

Restore or enhance degraded and impacted habitat

Immediate actions

While

local, state, federal and tribal governments are combining their efforts and

resources to address the critical needs of salmon, interim measures must be

taken immediately to prevent further harm to the species:

·

Use the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) to

specifically address salmon issues.

·

Use existing permitting requirements, such as shoreline

conditional permits, to protect habitat and mitigate project impacts.

·

Fund preservation and restoration projects.

·

Offer financial incentives to private landowners for

preservation of critical areas.

Improve plans and regulations

·

The state will adopt new shoreline guidelines based on

scientific information, designed to protect and enhance shorelines’ natural

functions and values. Proposed key features include establishing vegetation

management areas along all shorelines of the state, and increasing shoreline

stabilization by restricting new, and removing existing unnecessary, shoreline

armoring.

·

The state will update procedural criteria to provide

guidance on inclusion of best available science in critical areas ordinances

and giving special consideration to salmon protection and conservation. These

guidelines will assist counties and cities in making land use decisions and

eventually reduce the number of legal appeals.

·

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s (WDFW)

Priority Habitat and Species Program will be used to provide important

information on fish, wildlife and habitat to landowners, land use planners,

elected officials and other decision-makers. WDFW will assist local governments

in identifying land use activities likely to affect critical fish habitat and

will recommend measures to preserve or enhance fisheries.

·

State agencies will provide model ordinances to help local

governments address fish habitat protection and enhancement when in-filling

urban areas, conserving rural lands and reducing natural hazards.

·

Update and ensure implementation of stormwater management

programs (see Managing Urban Stormwater to Protect Streams chapter).

·

Revise floodplain management planning and funding criteria

to reduce damages to life and property, save public money, improve water

quality, restore habitat, and improve aesthetics and recreation. Coordinate and

integrate flood management with other planning and regulatory programs.

·

Use collaborative decision-making and improved scientific

tools to link transportation planning with land use decisions and salmon

recovery.

·

Support additional funding of local and state activities.

·

State agencies will provide other technical and financial

assistance to local governments on use of non-regulatory programs, such as use

of open space taxation, which offers property tax relief to private landowners

who preserve important natural resources.

·

Coordinate state, regional and watershed plans and programs

with related local programs.

Incentives and regulatory actions to improve performance and implementation and increase compliance

·

State, federal and local governments, tribes and private

entities will coordinate salmon recovery efforts and focus priorities on those

areas with listings and potential listings and high population growth.

·

State will link salmon-related funds to local regulations by

giving a preference to cities and counties that have taken actions that benefit

salmon recovery efforts.

·

The state will provide funds for local and state

implementation monitoring and enforcement programs with clear expectations of

results, and consequences if state agencies and local governments do not meet

the expectations.

·

Withhold capital facility construction funds from

jurisdictions that have not adopted Critical Areas Ordinances that include best

available science. Withhold funds for infrastructure and economic developments

that could potentially harm salmon or delay recovery efforts.

·

Local governments that fail to implement programs and

regulations that include best available science and give special consideration

for salmon protection and restoration will not be eligible to receive certain

protections granted under the Endangered Species Act.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

Monitoring

is an essential element of the strategy. The state will do the following to

assure that state and local actions achieve the expected results:

·

Develop benchmarks; monitor and publish progress in the

Governor’s State of the Salmon Report.

·

Incorporate monitoring and reporting programs into contracts

for salmon-related grants.

·

Continue to support and enhance data and information

programs, such as the limiting factors analysis, and use Geographic Information

Systems (GIS) to help local governments assess the impacts of existing and

future land use decisions, evaluate cumulative impacts and trends, and make

appropriate changes in land use practices.

·

Implement default actions. State agencies will use their

permitting, plans approval, and funding approval authorities and legal appeals

to stop or restrict developments if local governments fail to meet the

requirements to 1) review and update plans and regulations by September 1,

2002; 2) use best available science; 3) give special consideration to salmon

protection and conservation; and/or 4) if no progress is made toward protection

and restoration objectives.

Habitat is Key

MANAGING URBAN STORMWATER TO PROTECT STREAMS

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Studies

show that increased surface flow of stormwater caused by land development has

contributed to degraded salmon habitat. It’s generally more effective and less

expensive to prevent urban stormwater impacts on habitat than to retrofit

existing development. Degradation of habitat from urban stormwater can be

prevented or minimized by preserving high quality habitat or restricting where

development occurs. Stormwater management programs and practices are only

partially able to offset the degradation of salmon habitat caused by

development. Retrofitting or upgrading stormwater facilities can be very

expensive, take years to implement, and in most cases will not fully restore

the habitat that existed prior to development.

The

principal tools currently used by state and local governments to prevent or

mitigate the negative impacts of urban stormwater on salmon habitat are either

not fulfilling their goals to protect and preserve habitat or are not fully

implemented. These tools are:

·

The Growth Management Act (GMA) and Shoreline Management Act

(SMA) — the implementation of both acts has not focused on stormwater

management as a priority. They have not yet been sufficiently effective in

preventing stormwater impacts from new development by controlling the

geographic extent, location and intensity of development that degrades streams,

wetlands and estuaries.

·

The Puget Sound Water Quality Management Plan (PSWQMP)

stormwater provisions — these apply only to Puget Sound, are essentially

voluntary, and as of July 1998 have been fully adopted by only 31% of the

affected local governments. The guidance provided to local governments in the

current Puget Sound Stormwater Manual, particularly flow control requirements,

is outdated and inadequate to protect salmon habitat.

·

The National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

stormwater permit program — The NPDES stormwater permit program is a regulatory

tool for urbanized areas under the Clean Water Act (CWA), designed to achieve

both water quality and salmon habitat objectives. The permit requirements

currently apply only to Seattle and Tacoma and the unincorporated areas of

Snohomish, King, Pierce and Clark counties. The requirements do not apply to

all storm drainage systems within those areas.

·

The Hydraulic Project Approval (HPA) permit program — The

program covers the review and approval of development projects that affect

stream flows. However, the program has not been effective in monitoring and

preventing cumulative impacts of stormwater on salmon habitat.

Setting

priorities for stormwater management to protect and restore urban streams and

estuaries is necessary and must be done at the watershed level. A potential

model for setting stormwater management priorities within the context of local

watershed management has been developed and is being used by the Washington

State Department of Transportation (WSDOT).

Financial

and technical assistance is provided through many state and federal programs as

incentives for watershed management, habitat protection and restoration.

Although some technical and financial assistance for development of stormwater

management programs has been available from the state, substantial funding

needs related to local stormwater management are not yet addressed or are only

partially addressed. Transportation projects include significant costs to

mitigate impacts from stormwater. An estimated 5% of state and federal highway

construction funds are being spent on stormwater conveyance and treatment

systems and related items, such as land acquisition. Additional funding has

been provided by the 1999 legislature to WSDOT for stormwater.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goals

·

Prevent negative impacts on salmon habitat and water quality

caused by urban land development and changes in stormwater flow.

·

Mitigate impacts of urban stormwater and restore habitat

where impacts occur.

Objectives

·

Prevent urban stormwater impacts on salmon habitat by

preserving remaining high quality habitat, based on a priority system for

streams, wetlands and estuaries in urban and urbanizing areas.

·

Use growth management planning tools to control where and to

what extent development is allowed.

·

Encourage and support all cities and counties within the

Puget Sound region, and in other areas of the state where urban stormwater

contributes to the decline of salmon, to adopt and implement stormwater

management programs.

·

Research, demonstrate and implement improved designs for new

land development and redevelopment that will prevent urban stormwater impacts

on salmon habitat.

·

Retrofit stormwater controls for existing development and

rehabilitate streams in priority areas as needed to reduce stormwater impacts

on critical salmon habitat.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

Assistance and incentives for voluntary action

·

The Department of Community, Trade and Economic Development

(DCTED), the Department of Ecology (Ecology), and the Puget Sound Water Quality

Action Team (PSWQAT) will use financial incentives and technical assistance to

promote local governments’ adoption and implementation of the stormwater

program elements of the Puget Sound Water Quality Management Plan (PSWQMP).

Programs which maximize salmon habitat protection and restoration, and which

are consistent with local watershed management priorities, will have funds

directed to them from existing grants and loans.

·

The state, using financial and technical assistance, will

encourage local watershed management processes to identify high quality habitat

for preservation or protection through a variety of means, such as purchase of

development rights or conservation easements, and will establish priorities for

habitat restoration.

·

The state will work with federal and local governments to identify

new funding as an incentive to implement and enforce local stormwater

management programs and ordinances that are adopted and consistent with the

PSWQMP. Overall priorities for salmon recovery and priorities identified

through local watershed management processes or adopted by the Salmon Recovery

Funding Board will be the drivers for identifying specific funding needs and

for making funding allocation decisions.

·

Transportation projects impact salmon habitat by increasing

stormwater runoff. Funding is being provided to mitigate the environmental

impacts of road construction, to retrofit and upgrade stormwater controls

associated with state highways and roads and local transportation projects.

·

Current local authority and options for funding stormwater

programs need to be expanded. For example, the statutory authority of regional

and local jurisdictions to establish and fund stormwater utilities and

stormwater management activities needs to be clarified.

·

Ecology will enhance technical assistance on stormwater

management to local jurisdictions within the Puget Sound Basin and will begin

providing technical assistance outside the Puget Sound area. This is contingent

upon additional funding for technical staff.

·

State and local governments will collaborate to seek and

coordinate federal, state and local funding to support research and demonstrate

the effectiveness of best management practices for stormwater, including

building and site development practices. Opportunities for funding coordination

include the Centennial Clean Water Fund, Salmon Recovery Funding Board,

Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, and others.

State guidance and regulatory actions

A

key in the strategy for urban stormwater is to improve state guidance and

regulatory tools so they are accepted by the National Marine Fisheries Service

and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service as measures of the adequacy of

stormwater management programs in relation to salmon recovery and ESA

requirements. Over the next year the state will be working on the activities

described below:

·

DCTED will develop guidance to local governments on land

development practices and growth constraints necessary to preserve salmon

habitat and prevent stormwater impacts.

·

The Puget Sound Water Quality Action Team will upgrade the

elements of local stormwater program in the Puget Sound Water Quality

Management Plan (PSWQMP) by July 2000. Local governments in the Puget Sound

Basin will have two years to make their stormwater programs consistent with the

amended plan.

·

Ecology will improve and update the stormwater technical

manual and will expand its scope to include guidance for areas of the state

outside the Puget Sound Basin. After the manual is updated in the year 2000,

local governments will have two years to make their stormwater programs

consistent with the manual.

·

Ecology will strengthen NPDES permit requirements and

enforcement to incorporate standards for new development; require commitments

to retrofitting in priority areas and to operation and maintenance of

stormwater facilities; and to implement new expanded federal Clean Water Act

(CWA) requirements and enforce where appropriate.

·

The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) will

improve the Hydraulic Project Approval program’s capability to monitor and

prevent cumulative impacts from projects affecting stream flows.

·

Where the basic or comprehensive PSWQMP stormwater programs

have not been adopted by local jurisdictions as scheduled, state agencies will

consider which state authorities and regulatory tools should be applied and

enforced to protect salmon habitat.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

Adoption

and implementation of local stormwater programs consistent with or equivalent

to the PSWQMP and compliance with NPDES stormwater permits will be monitored.

The effectiveness of stormwater management practices, particularly new

practices, will also need to be monitored.

After

evaluating progress in achieving urban stormwater objectives as of September,

2002, the state will pursue the following actions for jurisdictions that have

failed to implement stormwater programs and, outside the Puget Sound region,

where stormwater has been identified as a limiting factor:

·

Mandate the adoption and implementation of the basic PSWQMP

stormwater program elements. This will require expanding NPDES stormwater

permit requirements to apply to any jurisdictions within Puget Sound or to

jurisdictions outside Puget Sound that have not adopted or implemented local

basic stormwater programs as called for in the Strategy.

·

Propose legislation amending the Shoreline Management Act or

Growth Management Act (GMA).

·

Further strengthen state water quality standards to

incorporate additional biological and physical criteria.

·

Amend the Washington Uniform Building Code to incorporate

building and site design standards and construction specifications.

Habitat is Key

ENSURING ADEQUATE WATER IN STREAMS FOR FISH

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Lack

of stream flow to sustain healthy production levels is a key factor

contributing to the poor status of wild fish stocks. Streams and rivers in

several basins used by salmon are over-appropriated, meaning more water is

being withdrawn for uses such as irrigation, when flows are naturally low and

when fish need water.

Allocation

of water in the state is based on a first-come, first-served basis. To address

the needs of fish and ensure that water is set aside for that purpose, instream

flows are established by rule for the amount of water required by fish. However,

most major development in and around water occurred before instream flows were

established, making water for fish “junior” in right to pre-existing water

diversions. In addition, fewer than one-third of Washington’s major rivers have

had instream flows set by rule, and the few streams that have instream flows

established frequently don’t meet the intended goals. For example, the existing

instream flows in the Cedar River in King County are not met 81 days out of the

year — and the number is increasing.

No

instream flows have been set in Washington since 1985. Meanwhile, the state’s

population has increased by 30% and nearly 20 salmon runs have been listed

under the Endangered Species Act.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goal

·

Retain or provide adequate amounts of water to protect and

restore fish habitat.

Objectives

·

Establish instream flows for watersheds that support

important fish stocks.

·

Protect and/or restore instream flows by keeping existing

flows and putting water back into streams where flows are diminished by

existing uses — especially illegal or wasteful uses or by poor land use

practices.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

Ensuring

adequate water for fish requires a collaborative, incentive-based approach, taking

immediate actions where needed, using strong enforcement of current

regulations, ongoing monitoring, and implementing default actions when

collaborative efforts fall short of expectations. This will be done within a

priority framework based on fish stock status, water availability and

conditions, and population growth. In addition, where gaps or legal conflicts

with the goals exist, appropriate legislative solutions will be actively

pursued.

Instream

flows will be established, protected and restored as follows:

Flows will be established in priority watersheds with ESA listings and in watersheds with healthy fish stocks and high population growth pressure.

·

Review and revision of existing instream flow rules,

including closures, will be a lower priority, but will be accomplished within a

set schedule, focusing first where flows are inadequate.

·

Until instream flows are set, either no new water rights

will be issued (except for public health and safety emergencies) or interim

instream flows will be set. Groundwater connected with surface water will be

treated as a surface water source, subject to the same restrictions.

Flows will be protected through effective monitoring and enforcement of established instream flows.

·

Future water right permits and changes to water rights, if

approved, will be conditioned with instream flows.

·

Stream gauges will be monitored to determine when instream

flows are not being met. Instream flows will be protected by regulating

affected water rights when the flows are not met.

·

Enforcement against illegal uses and restriction of

withdrawals from exempt wells contributing to flow problems will be

implemented.

Flows will be restored through a variety of means to put water back in streams.

·

Flow restoration will be the primary objective in watersheds

where flows are diminished by existing uses.

·

Each watershed supporting listed fish stocks will have in

place a comprehensive strategy for restoring instream flows.

·

Innovative tools, such as water banking, will be explored

and supported as appropriate.

·

Applications for grants of public funds for fish screening,

diversion passage correction, water conservation, etc., will receive priority

where the project includes a return of water for instream flows.

·

Public leasing or purchasing of senior water rights for

instream flows will be pursued aggressively.

·

Water conservation and water reuse will be emphasized to

augment stream flows and reduce the demand on streams and groundwater.

·

State approvals for hydropower projects will be conditioned

with instream flow releases. (See Hydropower and Fish: Pursuing Opportunities

chapter.)

·

Enforcement will be carried out against unauthorized

diversions, unauthorized uses and waste of water.

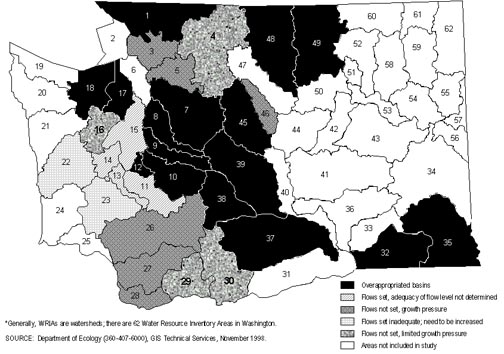

62

WATER RESOURCE INVENTORY AREAS (WRIAs)

IN

WASHINGTON

|

1 Nooksack |

16 Skokomish-Dosewallips |

32 Walla Walla |

48 Methow |

|

2 San Juan |

17 Quilcene-Snow |

33 Lower Snake |

49 Okanogan |

|

3 Lower Skagit-Samish |

18 Elwah-Dungeness |

34 Palouse |

50 Foster |

|

4 Upper Skagit |

19 Lyre-Hoko |

35 Middle Snake |

51 Nespelem |

|

5 Stillaguamish |

20 Soleduck-Hoh |

36 Esquatzel Coulee |

52 Sanpoil |

|

6 Island |

21 Queets-Quinault |

37 Lower Yakima |

53 Lower Lake Roosevelt |

|

7 Snohomish |

22 Lower Chehalis |

38 Naches |

54 Lower Spokane |

|

8 Cedar-Sammamish |

23 Upper Chehalis |

39 Upper Yakima |

55 Little Spokane |

|

9 Duwamish-Green |

24 Willapa |

40 Alkali-Squilchuck |

56 Hangman |

|

10 Puyallup-White |

25 Grays-Elokoman |

41 Lower Crab |

57 Middle Spokane |

|

11 Nisqually |

26 Cowlitz |

42 Grand Coulee |

58 Middle Lake Roosevelt |

|

12 Chambers-Clover |

27 Lewis |

43 Upper Crab-Wilson |

59 Colville |

|

13 Deschutes |

28 Salmon-Washougal |

44 Moses Coulee |

60 Kettle |

|

14 Kennedy-Goldsborough |

29 Wind-White Salmon |

45 Wenatchee |

61 Upper Lake Roosevelt |

|

15 Kitsap |

30 Klickitat |

46 Entiat |

62 Pend Oreille |

|

|

31 Rock-Glade |

47 Chelan |

|

Locally based collaborative watershed management efforts will be supported if they address establishing, protecting and/or restoring instream flows within a reasonable time.

·

Solutions will be tailored specifically for each watershed.

·

Deference will be given to collaborative watershed

management efforts to establish, protect and restore instream flows, but not if

delays risk the extinction of wild salmonids.

Certain requirements, intended to apply in all watersheds with ESA listings or potential listings, will be implemented first in the highest priority watersheds. The requirements include:

·

Metering and reporting of diversions and withdrawals by all

water users.

·

Implementation of water conservation and use of reclaimed

water where feasible.

·

Strategic enforcement against illegal uses (including

wastage).

Immediate actions will be pursued on a priority basis:

·

To avoid further decline in fish stocks, the state will

collaborate with local groups to identify and implement actions that need to be

taken immediately.

·

Immediate actions could include restricting use of exempt

wells, enforcing against excessive waste of water and illegal water uses, and

requiring strict water conservation measures and water use standards.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

The

state will closely monitor the progress of both its own efforts and that of

local watershed groups developing solutions to instream flow problems.

Performance indicators to be tracked and reported include:

·

Number of watersheds (Water Resources Inventory Areas -

WRIAs) with instream flows established by rule.

·

Number of watersheds with instream flow protection and/or

restoration programs implemented.

·

Number of watersheds with adequate instream flows (i.e.,

meeting the needs of fish).

·

Default actions will be identified and used when a local

collaborative process fails or is unable to address the establishment,

protection and restoration of instream flows in a timely manner.

·

Default actions could include closing or withdrawing basins

from further appropriation, restricting the use of exempt wells, mandating the

implementation of water conservation and water use efficiency practices, and

pursuit of additional state, federal and local regulatory avenues where

appropriate.

Habitat is Key

Clean Water for Fish: Integrating Key Tools

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Many

Washington waters are not clean enough to meet standards for water and sediment

quality and are causing harm to salmon. Although municipal wastewater and

industrial discharges require increasingly intense treatment under the Clean

Water Act (CWA), many water bodies still fail to meet standards. Point and

nonpoint sources of pollution, individually and in combination, affect aquatic resources,

especially fish. Pollution sources include agriculture, forestry, stormwater

and municipal discharges, as well as runoff that carries bacteria, toxins and

excess nutrients.

Washington

is currently launching two significant and parallel environmental initiatives:

development of a statewide plan for salmon recovery and development of cleanup

plans for polluted water bodies. These two initiatives are governed by separate

federal acts — the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and the Clean Water Act (CWA) —

that have historically been powerful tools for change, with varying degrees of

success. The two acts have seldom been applied concurrently to the same

activity or issue. But because water quality and habitat conditions are largely

governed by human activities, it is imperative that the state and federal

agencies administer these laws and develop the salmon recovery and water

cleanup plans in a coordinated, consistent and complementary fashion.

The

federal Clean Water Act requires the state to establish standards for specific

pollutants in water bodies, prepare a list of water bodies that do not meet

water quality standards, and develop water cleanup plans, or Total Maximum

Daily Loads (TMDL), for each of the polluted water bodies. The implementation

of these requirements is critical to protection and restoration of salmon

habitat.

The

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the state of Washington were sued for

allegedly not making satisfactory progress in assessing water quality and

developing water cleanup plans. The plaintiffs and the agencies negotiated a

settlement agreement and consent decree that was filed in federal court in

January, 1998.

The

primary outcome of the settlement was the establishment of a schedule for the

state to develop and begin implementing cleanup plans for each of the nearly

670 marine and freshwater bodies identified on the state’s 1996 pollution list.

The

cleanup plans, or TMDLs, are a calculation of the capacity of a water body to

assimilate pollution without violating water quality standards, and an

allocation of that capacity to various point and nonpoint discharges.

Implementation plans to achieve reductions that address timing and methods of

pollution control, tracking, monitoring and adaptive management are required.

The

majority of the cleanup plans will address pollutants that adversely affect

salmonids, including toxics, as well as more common pollutants such as elevated

temperature and depleted oxygen.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goal

·

Restore and protect water quality to meet the needs of

salmon.

Objectives

·

Revise and implement water quality standards to respond to

aquatic ecosystem needs.

·

Implement water cleanup plans for water bodies in ESA listed

areas first.

·

Implement nonpoint source “best management practices,” and

nonpoint action plans.

·

State and federal agencies will integrate the Endangered

Species Act (ESA) and Clean Water Act (CWA) to offer agencies and landowners a

predictable, practical and coordinated process to meet the needs of both laws.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

Ensuring

clean water for fish requires agreement on a common set of performance measures

(e.g., water quality standards), implementation of conservation practices

through regulatory and voluntary actions, and monitoring.

Water

quality standards

·

The state will adopt, collaboratively with the Environmental

Protection Agency (EPA), the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) and the

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), revised surface water quality

standards.

·

The state will implement the revised standards, relying on

water cleanup plans, waste discharge permits, nonpoint pollution action plans,

enforcement and funding.

Water

clean-up

·

The state will accelerate the development and implementation

of water cleanup plans for water bodies listed under ESA and CWA. This will be

done in conjunction with other watershed planning efforts underway at state and

local levels, including planning under the Watershed Planning Act.

·

The majority of cleanup plans will address pollutants that

adversely affect salmon such as elevated water temperature and sediments.

Priority will be given to development of water cleanup plans that protect

salmon.

·

To implement the cleanup plans the state will rely primarily

on existing regulatory and voluntary programs, such as waste discharge permits,

programs for cleaning up contaminated sediments, nonpoint source “best

management practices,” inspections and enforcement. Existing water quality

programs will be better focused and enhanced to implement cleanup plans and

improve water quality.

·

Additional funding to implement the settlement agreement is

needed. Ecology will continue to work with legislative committee members, their

staffs and consultants, as well as other agencies and stakeholders, to identify

and resolve program and funding concerns.

·

The state will finalize and submit to EPA and to the

National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) Washington’s Nonpoint

Management Plan as required by the Clean Water Act and Coastal Zone Act

reauthorization.

·

The state will enhance the implementation of nonpoint source

“best management practices” by state and local governments and private

landowners to ensure a focus on and a commitment to meeting water quality

standards.

·

The state will encourage voluntary activities to address

water quality problems. Immediate corrective and compliance actions will be

taken by the state where appropriate.

ESA

and CWA integration

·

The focus will be on reaching a commitment of certainty for

landowners and governmental agencies under the ESA and CWA. Certainty will

require agreement on the goals, science-based criteria and targets, timeframes

for implementation, and results expected.

·

The state departments of Ecology, Fish and Wildlife, and

Natural Resources will continue discussions with regional representatives from

the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS), the U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service (USFWS), the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and with tribes to

examine the issues, develop options and identify solutions for integration of

ESA and CWA.

·

The Governor’s Office will seek agreement from the White

House Administration with the solutions reached regionally. Ecology and other

state agencies will implement the agreements reached regarding ESA and CWA

integration.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

The

state will:

·

Track progress toward implementation and resolution of the

Endangered Species Act and Clean Water Act integration issues.

·

Continue to conduct ambient monitoring and perform water

quality assessments every two years, or as required by EPA, using its own data

and other available data, to determine compliance with water quality

standards.

·

Along with local governments, identify and implement

opportunities for enhancements to existing water quality programs to improve

and prevent degraded water quality.

·

Annually track the development and completion of cleanup

plans against the targets set in the settlement agreement.

·

Conduct effectiveness monitoring to evaluate the success of

water cleanup implementation strategies in meeting water quality standards. If

progress toward meeting water quality standards is inadequate, the

implementation strategies will be evaluated and revised.

Should

the state not develop the required water cleanup plans, the default is for the

federal Environmental Protection Agency to develop and implement the required

plans.

If

the ESA and CWA integration issues are not satisfactorily resolved, the state

would likely lose support for completing the water cleanup plans. The plans

would then be developed by the federal EPA. If satisfactory progress is not

made, it is also likely that further legal action would be pursued by the

plaintiffs in federal court.

Habitat is Key

Fish Passage Barriers: Providing Access To Habitat

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Salmon

need access to spawning and rearing habitat. More than 100 years of human

development in Washington’s rivers and streams has created numerous physical

barriers, interrupting adult and juvenile salmonid migrations in many

watersheds. Barriers include culverts, diversion dams, debris jams, dikes,

stream gradient, and other human-caused stream changes.

There

are approximately 170,000 miles of public and private roads in the state. Only

a fraction of these roads have been inventoried for fish passage barriers, and

most of the inventories that have been completed are not prioritized from a

watershed perspective.

Design

of barrier corrections is site specific. There is limited availability of

individuals with the expertise to organize and conduct fish passage inventory,

design and construction.

Funding

for barrier correction in the past has been insufficient to address the

problem. The median barrier correction cost is approximately $100,000. It will

take time and funding to correct the multitude of barriers around the state;

however, barrier corrections and screening programs are being implemented by

state, federal and local governments, as well as private landowners.

II. Goals and Objectives: Where do we want to be?

Goal

·

Ensure that usable or restorable habitat is accessible to

wild salmon by removing existing barriers, preventing creation of new barriers,

and screening all diversions.

Objectives

·

Complete watershed-based inventories and prioritization of

fish passage problems.

·

Correct existing barriers and screen diversions and prevent

new passage problems.

·

Create a comprehensive long-term funding strategy that uses

federal, state, local and private dedicated funds and project mitigation funds

to expand correction programs and monitor effectiveness of those programs.

·

Use volunteer-based organizations where appropriate to gain

the best use of limited funds.

·

Develop better understanding of fish passage needs,

especially juvenile salmon migration habits and needs.

·

Integrate fish passage and screening activities into

implementation of watershed planning and other planning and restoration

efforts.

III. Solutions: What is the route to success?

Although

barrier correction programs are in place, a comprehensive program is needed to

better understand the extent of the problem, to determine the priority of

addressing fish passage versus other limiting factors in a particular

watershed, and to monitor the effectiveness of barrier correction programs. To

assure that the goal is met, the following actions will be taken:

Watershed-based inventory and prioritization:

·

Use the manual recently completed by the Washington

Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) that details the protocol for locating,

assessing and prioritizing barriers, and for conveying the necessary

information to WDFW for incorporation into a centralized database.

·

Expand inventory and prioritization of barriers on state

lands and facilities (i.e., state highways).

·

Support fish passage inventory and prioritization efforts by

counties and cities.

·

Implement the element of the Forest and Fish Report which

calls for inventory and assessment of barriers caused by forest roads. Fish

passage concerns will also be included in the state Forest Practices Rules.

·

Complete the limiting factors analysis for watersheds within

the seven Salmon Recovery Regions.

·

Continue to collect information and data on known and

potential barrier and screening problems and locate them on a Geographic

Information System (GIS).

State actions for correcting and preventing fish passage problems:

Address correction and prevention of fish passage problems comprehensively.

·

The state will collaborate with the tribes, federal and

local governments, irrigation districts, public utility districts and private

landowners to identify, correct and/or remove human-caused fish passage and

screening problems in freshwater, floodplain and estuarine habitats. The effort

will also include continuous monitoring and maintenance of existing structures.

This effort will be integrated into existing watershed management efforts.

Standardize fish passage design.

·

WDFW engineers have completed a design manual. The agency

will facilitate training and technical assistance to those conducting design work

on fish passage barrier corrections.

Better understand fish passage and screening needs.

·

Continue ongoing training and education programs to make

professionals aware of current fish passage and screening statutes, barrier

identification, prioritization and design criteria.

Advance knowledge about juvenile migration and design flows for passage.

·

Culverts that are currently designed for adult migration may

be insufficient for juvenile migration. For some species, little is known about

the needs and extent of upstream movement and timing of juvenile salmonids.

This knowledge is essential to the design of a comprehensive recovery strategy

and determination of design flows for passage. To increase potential for

success, juvenile passage design standards need to be developed and additional

design options made available to those designing and conducting passage

correction work.

Enhance efforts to streamline permitting process.

·

House Bill 2879 passed in the 1998 legislative session

allows permit streamlining for salmon habitat recovery projects, enabling some

projects to move forward quickly. (See Permit Streamlining chapter.)

Use volunteers to support state and local efforts.

·

The state and its partners must promote correction efforts

through the direct involvement of citizens who live and work within watersheds.

The state will enlist volunteers and coordinate programs that involve hands-on

salmon restoration efforts combining stream restoration with barrier removal

and fish screening.

Use of enforcement and incentives.

·

The state will cost-share installation of screens to reduce

hardships to landowners. Projects integrated with other watershed efforts may

receive additional priority. A regulatory approach will be used in cases where

harm to salmon is evident and the landowner resists compliance.

Implement a comprehensive funding strategy.

·

State and federal funding has been provided for fish passage

barrier identification and removal. State and federal funding will be

coordinated and targeted through the newly created Salmon Recovery Funding

Board to address priorities. Funding for a fish passage correction program on

state facilities (WSDOT highways and roads) provided by the legislature will be

also coordinated.

IV. Monitoring and Adaptive Management: Are we making progress?

Monitoring

the success of barrier removal projects has had little attention. Baseline and

post-correction data must be collected and analyzed through an established

funded program. The monitoring program will include the following:

·

Establish a procedure for review of corrected problems and

progress of correction programs to ensure effectiveness.

·

Sample corrected barriers to determine upstream and

downstream migration by adults and juveniles and sample screened diversions to

ensure fish protection.

·

Standardize fish barrier and diversion databases, coordinate

data collection and centralized data access, and coordinate work among

watershed planners, road managers, resource agencies, tribes and

non-governmental organizations within watersheds. The priorities of all

barriers and diversions can be compared and the most cost-effective projects

done first.

·

Develop and maintain a GIS-based, Internet accessible

database of fish blockages and diversions statewide.

Harvest

Harvest Management to Meet the Needs of Wild Fish

I. Current Situation: Where are we now?

Fish

harvest management plays a critical role in developing and implementing a

comprehensive strategy for protecting and restoring wild salmon. Greater

harvest controls are being undertaken to complement habitat protection and

restoration efforts. The Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) and

northwest treaty Indian tribes developed the Wild Salmonid Policy (WSP) to

provide leadership and a commitment to fish management that ensures sufficient

wild spawners escape fisheries and reach spawning grounds. In addition, the

Pacific Fishery Management Council in 1998 adopted a revised Salmon Management

Plan, affecting stocks in California, Oregon and Washington that strengthened

requirements for stock status monitoring and put in place strict rules for

preventing overfishing, and correcting overfishing when it occurs. Regional

state-tribal fishery management plans throughout the state are being reviewed

and revised in order to implement harvest and hatchery management plans

consistent with wild salmonid recovery.

Many

Washington salmon populations are abundant and have surplus production that can

be harvested to support the many commercial, cultural, economic and

recreational benefits and values traditional in the Pacific Northwest. We must

ensure that, while pursuing those healthy, harvestable fish, harvest occurs in

ways that minimize impacts on depleted populations and provide adequate

spawning populations. For example, the presence of adipose-clipped hatchery

steelhead, coho and chinook in fisheries can and are providing the ability to

selectively harvest hatchery fish with lower impacts to wild fish.

Still,

we must be mindful that it’s not necessarily how many fish that spawn (though

there clearly must be adequate numbers of spawners), but how many adults are

produced from those spawners that determines whether fish populations will

rebuild. Where habitat productivity and access are adequate and the genetic

resources of the wild population have been maintained, sufficient numbers of

wild spawners to the stream will recover wild stock abundance. However, where

habitat is poor, providing an adequate number of spawners may not be as

important as increasing the productivity of those spawners in their habitat.

For this reason, it is vital that harvest management and habitat management be

closely linked.

To

allow sufficient numbers of wild spawners to escape harvest, managers use a

variety of tools to determine the total estimated run size and the allowable

numbers of fish that can be caught. The key to sound harvest management is the

ability to: 1) target harvest on wild stocks with surplus production, and 2)

produce and harvest hatchery fish in ways that protect weaker stocks until

their productivity improves. Recent actions to improve harvest management

include:

·

Comprehensive management planning by the state and Puget

Sound tribes to develop a species management framework for coho, with

accompanying guidelines on exploitation rates and fishery regimes. This is one

of the first salmon species activities in Washington to incorporate harvest,

hatchery and habitat issues into one comprehensive plan.

·

State and tribal staffs are currently developing a

Comprehensive Chinook Management Plan for Puget Sound. This framework will

provide the basis for the National Marine Fisheries Service to develop a “4(d)

rule” under the Endangered Species Act (ESA) that authorizes and limits “take”

that will actively support the recovery of Puget Sound chinook under ESA and further

rebuild runs to levels that will provide sustainable harvest opportunities. A

comprehensive review and development of appropriate fishery impact guidelines

is a cornerstone of this effort.

·

U.S. — Canada Pacific Salmon Treaty: In 1998 the “Locke/Anderson

Agreement” between Washington and Canada broke through a major impasse in the

Pacific Salmon Treaty process by striking an agreement that: (1) reduced

impacts on Fraser River coho; (2) reduced impacts on Puget Sound chinook; (3)

will provide Canadian support for Washington’s mass marking and selective

fisheries initiative; and (4) provides for a more active collaboration between

the two countries in planning annual fisheries to protect depleted salmon

populations. This breakthrough was followed in 1999 by newly renegotiated

fishing agreements between the two countries. The new annex significantly

reduces Canadian chinook fishery impacts on Puget Sound stocks from the

treaty’s original provisions in 1985, and establishes for the first time an

abundance-based approach for determining Canadian coho harvests.

·

The “U.S. vs. Oregon Columbia River Fisheries Management

Plan” is currently being reviewed and negotiated by the states, tribes and

federal government to implement appropriate changes in harvest and hatchery

approaches.

·

Fisheries that differentially harvest healthy stocks or

species have been expanded from past years. The first use of the

adipose-clipped mass marking for marine coho salmon sport fisheries occurred in

1998 in the Columbia River and adjacent marine area. In 1999 these selective

recreational coho fisheries were expanded to all Washington ocean areas, the

Strait of Juan de Fuca and South Puget Sound.

·

In 1998 and 1999, most chinook retention was prohibited in

the Strait of Juan de Fuca and northern Puget Sound fisheries because hatchery

and wild fish could not be differentiated.

·

Puget Sound commercial sockeye fisheries in 1998 were

constrained to limit impacts on other species, notably chinook. These

limitations continue in 1999 with new fishing measures required to reduce

release mortalities by non-Indian purse seine fishers and a log book program

implemented in non-Indian commercial fisheries, verified by WDFW on-water

bycatch monitoring efforts.

·

Commercial salmon fishery restructuring: WDFW, in

cooperation with NMFS, completed a $4.5 million salmon license buyback program

in 1998 that continued to address the over-capitalization in Washington’s

commercial fishing industry. The program retired 391 licenses, representing a

17% reduction in current Puget Sound licenses. Furthermore, as a result of

recent Pacific Salmon Treaty renegotiations, WDFW and the commercial

stakeholders are poised to further reduce the commercial fleet to a sustainable

level.

·

WDFW, as mandated in ESHB 1309 and SB6150, recently

completed an evaluation of the capacity of current and alternative fishing

methods and gears to release non-target species with low mortality and